If you care about our National Parks, wilderness, or public lands, in general, then you must be vigilant about what is happening in Washington D.C. and what your elected officials are doing. Most importantly, you should know how to fight for the environment in Washington DC, which means how things work and how to be a good advocate.

If you love and use federal lands, you should be worried about their future, and you should fight for their interests.

Mother Nature may be cold and uncaring, but that doesn’t mean you should be.

As a background, I used to work in Washington D.C. where I spent five years working for a senior member of Congress. For at least two of those years, I worked directly on environmental issues for the Chairman that controlled enviro spending in the House of Representatives.

Me working late on the House Floor, Blackberry in hand!

This is a topic I care a great deal about, am intimately familiar with, and think we should all be a little more involved with and aware of.

The Average American

Only about 60% of all eligible voters turn out to vote in presidential elections (~130 million people) — that means a huge number of people don’t even care enough (about any issue–whether it’s the economy, abortion, gun control, or the environment) to vote.

During mid-term elections, those elections for the House and Senate held between four-year presidential terms, that turnout is only about 40% (~90 million people).

So we can see that relatively few people are politically active (particularly when you consider voter registration numbers).

But when you consider how many people loosely pay attention to the political process and what happens in Washington D.C. in the time between elections, the reality is that the number drops even more sharply.

I haven’t seen any estimates for that number, but we’ve already seen how the trend is moving downward.

Sadly, I can tell you from first-hand experience observing town hall meetings, taking phone calls, and responding to constituent correspondence, that even the majority of Americans who do kind of pay attention between elections are often misinformed about what happens in the corridors of power and how things actually work.

That statement goes for both the Left and Right.

I know, we’re all busy leading our lives, going about our day, and trying to get by — but there is really no excuse to follow celebrity gossip or reality TV programming closer than the political process in Washington D.C.

I’ve never understood the idea that nothing happens in D.C. because GOOD and BAD things happen on an almost daily basis — things that have a real impact on the future of our public lands (among everything else).

Besides, when you get into it with the behind-closed-door machinations, power grabs, scandals, and more, it is far more interesting (and important) than an episode of [insert terrible reality TV series here].

How D.C. Really Works

The President always gets all the attention and focus, but everyone also tends to inflate the powers of the President because the President is the most visible and high profile elected official.

Any President will, at times, receive an undeserved amount of credit for good things and an undeserved amount of blame for bad things — often over things they have little to no control over.

The President is undoubtedly important and has a number of real powers, but in terms of actual spending and legislation, that role is mostly starting the conversation, acting as the loudest voice in the room, and then acting as a sort of final yes or no (singing it into law or vetoing the bill for changes).

Thousands of bills (good and bad) may be introduced in a given Congress, but most never see the light of day — and most activists focus their time and attention on the threat/benefit of these things that aren’t even moving while ignoring the big important things: money and the annual budget.

In terms of the budget, the President will set the tone, overall objectives, goals, and some guidance on specific issues, but the President is not involved in the nitty-gritty of budget proposals and spending unless it’s a pet project.

There can be good presidents or bad presidents, but everything in DC still has to go through the same processes, regardless of who is in the White House.

The real decision making for almost everything goes through a complex series of procedures. That is how the sausage gets made.

Things will be simplified somewhat, but here’s how it works in broad strokes:

Budget Proposal

The President will send forth his budget proposal which contains big picture guidance across every department and agency.

Individual Departments send more specific budgetary proposals to Congress based on the President’s guidance — this is where the power of Cabinet Secretaries comes into play, as they make the micro proposals based on the macro guidance.

So, remember, it isn’t just the President’s perspective or position on X or Y — it’s also the perspective of the people he puts into power, like the Secretary of the Interior, and who do not answer to voters.

Not All Congressmen are Equal

At this point, the budgets are only proposals… Now is when Congress plays its role as legislators.

Power among individual members of Congress is NOT equal on any given issue:

- The minority party doesn’t have as much power as the majority.

- Newcomers don’t have as much sway as senior members or members of leadership.

- Certain committees are much more powerful or influential compared to others.

- Different committees (and sub-committees) have jurisdiction over different subject matters.

Your Member of Congress may not have much of a voice when it comes to the environment if they are part of the minority party, are a relative newcomer, or don’t serve on the appropriate committee(s). Worse if they are all three.

You may think individual members exerting an outsize influence on issue areas isn’t right or fair, but, the reality is, it makes a lot of sense.

The idea is that these members are immersed in particular areas, and are (or become) extremely knowledgeable over their portion of the budget… The higher you move up any chain or organization, the less they will know about details.

This is true for defense spending, environment, agriculture, transportation, and so on.

Like any other place of employment, certain people have responsibility over just a small portion of the overall organization and are expected to have much more in-depth knowledge about their particular areas of jurisdiction–not unlike calling in different experts to build different parts of a house from plumbing, framing, or electricity.

A jack of all trades is a master of none.

He Who Controls the Money…

The Appropriations Committee is one of the most powerful committees in either the House or Senate because they control discretionary (non-entitlement) spending across the entire government. The constitutional basis for the Appropriations Committee is outlined clearly within the Constitution.

They control the “Power of the Purse” so to speak.

This means they can help the things they like to flourish with increased spending, or they can even let authorized programs wither and die by restricting spending. They can follow the directives of the President or (within limits) they can do their own thing.

The Appropriations Committee is divided up into subcommittees that control individual spending bills… The Subcommittee on the Interior and Environment (House link – Senate link) is the one chiefly responsible for environmental issues as it funds:

- the National Park Service (NPS),

- the Bureau of Land Management (BLM),

- the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS),

- the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS),

- the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),

- the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE),

- among others.

Every subcommittee is made up of just a handful of congressional members (~11 for Interior) from the full committee (~50 members), and these are the elected officials that exert the largest influence on these issues.

Collectively, they have the power to do a lot. It doesn’t matter whether it is clean energy, protection for endangered species, protecting clean water or air, or funding the backlog of maintenance work in National Parks.

The spending bill will pass the vast majority of its life in subcommittee, as those members perform oversight and hold hearings and assemble the overall package, nitpicking over the smallest of details, final budgetary numbers, and introducing some policy provisions or direction (saying what funds can or cannot be used for, for example).

If other members of Congress (such as those in leadership or general allies) have priorities they want to be reflected in the final bill, that will be done by proxy throughout the committee process… Just good old fashion phone calls or informal conversations on the floor advocating on behalf of an important environmental issue to those who are actually calling the shots.

Moving up the Food Chain

After leaving the subcommittee with a favorable vote, it will pass fairly quickly through the full Appropriations Committee for a vote (seeing a limited number of amendments), then later go to the floor for a vote from all members of Congress.

With each step through the process, members become less involved and less influential, and the fine details become much more difficult to change.

Once a bill reaches the floor, almost all the work has been done and decided… IE a huge multi-billion dollar environmental spending bill is presented for a vote to all members of Congress and is almost a done deal, time to say yes or no.

(This is also why sometimes members end up voting for parts of things they aren’t necessarily in favor of, because they are packaged inside of a larger bill).

Nine times out of ten, if a big important bill like this has been brought to the floor, it is because Leadership is confident that it will pass. All of the hard work has been done earlier in the committee process — the floor is essentially just for the final vote and where members can speak “on the record” but can’t make significant changes.

Riders – It’s Not Just About Money

Riders — policy provisions that have little or nothing to do with spending and the budget — can usually be inserted at any time during the process, though most frequently before they get to the floor.

They are called “riders” because they should normally go through the authorizing committees, but can be attached to bills like appropriations which will (in most years) eventually pass in some form or another, which they can “ride” into becoming law.

Whereas, if they had gone through the normal process and been given a straight vote they may have been much more difficult to pass if they hadn’t been pack packaged together.

This is how sneaky things can become law, for example, provisions that:

- prevents the EPA from requiring the reporting of greenhouse gas emissions from manure management systems,

- exempts livestock grazing permit renewals from environmental review,

- prevents implementation or enforcement of a threatened species listing under the Endangered Species Act,

- blocks EPA from enforcing rules to limit exposure to lead paint,

- and pretty much anything else you can think of.

Not all riders are necessarily bad, but the point here is that there is a tremendous amount of power within appropriations bills to control not just final dollar amounts but far-reaching policy decisions that affect the environment.

Where the House and Senate Meet

The House and Senate both come up with their own different bills, going through the same process, with their own individual budgetary numbers which can differ by a little or a lot as well as their own policy directives.

Once both are passed, they go into conference (negotiations) to come up with bills that are identical in language and dollar amounts. This means balancing the priorities or direction between both Chambers, which can be a somewhat time-consuming and complicated process.

Throughout this entire process, the Subcommittee members (particularly the Chairmen of the Subcommittee and the full Committee) exert the greatest deal of influence on the final result, because they have the greatest vested interest in the bill.

The finalized bill is sent back once again for a normally quick and painless vote by both chambers and it is then, and only then, after all of those processes have taken place that a bill will go back to the President for him to sign or veto.

Once it gets to his desk, the President is NEVER going to be analyzing every program, every policy provision or rider, every dollar amount, and so forth. He will be looking at whether it is on the whole within what he would consider acceptable or not.

Congress and the President may disagree, and the President can push back. Congress can push back again. It is over these funding bills where Government Shutdown situations flare up from time to time. But those instances normally happen when Congress is controlled by one party, and the President is from another.

So in the end, any individual president holds relatively little control over the nitty-gritty details of our environment, whereas a small group of people (more on who they are later) holds an extraordinary amount of influence over it.

Compromises Must Be Made

In every part of the process, there is no person (staff or members) who thinks “this bill is 100% perfect, I wouldn’t change a thing” — it is always a question (no matter what side of the aisle you are on) of whether this is as good as you think it can get under the current environment, or whether it is on the whole better than it is bad and contains no absolute dealbreakers.

Compromises are made among committee members, compromises are made between the House and Senate, and then compromises are made between both chambers and the President.

Politics is ALWAYS an act of compromise to achieve the final result.

Just imagine trying to decide what restaurant to eat at with your entire extended family and how complicated that would be as you try to appease the demands and desires of everyone. Let’s say you came to an agreement about the local burger joint…

But then imagine that instead of everyone being able to order their own individual meal and what they want, that everyone had to order the exact same thing at the restaurant. Meaning that everyone has to come to an agreement about the same toppings, sauces, how well done, etc., for all the hamburgers.

Tough, right?

Now, instead of your extended family, replace them with a few hundred elected officials with competing interests and demands, a tendency toward showmanship, grandstanding, and seeking out positive press coverage, and you’ll see just how complicated things can get.

For better or worse, things are never as black and white and easy as they might seem in Washington D.C.

What Does This Mean After a Presidential Election?

So if the real power is in the hands of Congress, what does all this mean in terms of who we back as president?

It means that a President doesn’t necessarily pose as direct of a danger to the environment as some may think nor does another President hold all the answers for the environment.

Let’s not forget, the President changes every 4 to 8 years, but the general makeup or ideology of Congress can change much slower (individual members can serve much longer and Congressional majorities can span different presidents and parties.

The fact of the matter is, an environmentally friendly president can act as a roadblock against an environmentally unfriendly-Congress. Just as an environmentally unfriendly president can block an environmentally friendly congress.

The danger then comes when an environmentally unfriendly or indifferent president oversees an environmentally unfriendly Congress.

If you care about them, you should fight for them, advocate for them. Don’t sit by silently while they are marginalized.

Interior Appropriations Subcommittee

The people who are going to have a real and lasting environmental impact (for good or bad) are sitting in Congress, not the White House.

Below are the people who are really controlling overall environmental policy and spending decisions.

If you live near or within the districts of the following members, then your voice matters more than other Americans in this matter, and you should be particularly active in sharing your opinion or seeing that these people lose reelection if they do not share your views on the environment.

Chairs (Majority) or Ranking Members (Minority) are the most powerful within their given subcommittee. Remember that members in the Minority have much less power and influence (though they have some).

Senate Republicans

- Lisa Murkowski, Alaska, Chairwoman

- Lamar Alexander, Tennessee

- Roy Blunt, Missouri

- Mitch McConnell, Kentucky

- Shelley Moore Capito, West Virginia

- Cindy Hyde-Smith, Mississippi

- Steve Daines, Montana

- Marco Rubio, Florida

Senate Democrats

- Tom Udall, New Mexico, Ranking Member

- Dianne Feinstein, California

- Patrick Leahy, Vermont

- Jack Reed, Rhode Island

- Jon Tester, Montana

- Jeff Merkley, Oregon

- Chris Van Hollen, Maryland

House Republicans

- David Joyce, Ohio, Ranking Member

- Mike Simpson, Idaho

- Chris Stewart, Utah

- Mark Amodei, Nevada

House Democrats

- Betty McCollum, Minnesota, Chair

- Chellie Pingree, Maine, Vice Chair

- Derek Kilmer, Washington

- José E. Serrano, New York

- Mike Quigley, Illinois

- Bonnie Watson Coleman, New Jersey

- Brenda Lawrence, Michigan

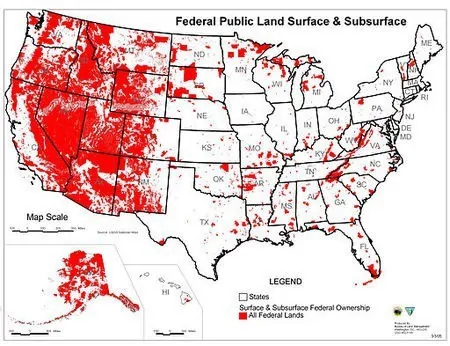

Thoughts on Federal Public Lands

A shockingly large number of these subcommittee members hail from states that don’t even have significant amounts of federal lands, but who are more concerned with maximizing natural resource extraction on those lands.

This is pretty much putting the fox in charge of the hen house.

Public lands should not be judged as to how many dollars can be extracted out of them, or whether they are a net contributor to government revenue or a net user of government spending.

This is the folly of the “government should be run like a business” model. The government cannot be run like a business or a private household. Most National Parks don’t contribute to the revenue and are not moneymaking ventures.

Indeed, it is but a few National Parks (like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon) that help to subsidize less popular parks — in the same way that bigger, more prosperous states contribute tax dollars and subsidize smaller, poorer states.

We shouldn’t cut or privatize Great Basin National Park because it costs us taxpayers money, any more than we should cut Mississippi from the USA because they cost everyone else money.

The bottom line cannot be the only consideration when it comes to the environment.

How to be an Effective Environmental Advocate

Personally, I’d like to see fewer complaints about what the President is or isn’t doing, and more people complaining about what their Congressman or Senator is or isn’t doing (but to do that, you’ve got to pay closer attention).

Even people with the best of intentions sometimes don’t know how to effectively advocate for their causes. Having spent so many years working in D.C., here are a few tips to actually have your voice heard:

Pay Attention

This one should be obvious, but if you don’t know what is happening then it is hard to be an advocate. Maybe for you it’s the National Parks, BLM lands, hunting and fishing on wildlife refuges, or whatever.

Stay tuned to what is happening WHILE it happens — not just after something bad has happened. Advocacy groups (more on that below) are a good way to stay somewhat informed.

Contact Your Congressman

Digital Communications

Don’t sign silly online petitions, that is about the laziest thing you can do. Don’t submit generic form letters through online advocacy sites. Emails are the least effective way to advocate. Staff will pay the LEAST amount of attention to these methods.

Commenting via their public social media accounts would be best if you can’t do anything beyond digital — although that can be dismissed as well since it is easily susceptible to comments from people who aren’t constituents.

It goes without saying but members pay closest attention to those who actually are within their voting district. Trying to push Senators or Representatives from another state will not have much influence, and you’re actually taking away resources (time, attention, etc) from the people they were elected to represent.

Making Calls

Calling is a step up — but if you call, do NOT read from a script you got online. I can speak from experience, if you read from talking points, you will be tuned out as soon as they’ve got the idea so they can continue multitasking on the computer.

If your message doesn’t have an impact on the staff or intern you are talking to, you can’t honestly expect it to reach your Congressman. Formulate your own informed thoughts and insightful questions — it is much easier to talk to someone who calls in with a curious, inquisitive tone versus someone who is rude and confrontational.

Staff are busy, they don’t really want to talk to you, but you can (and should) engage in conversation with them. If you don’t like the responses you are getting from the person who answered, don’t ask to speak to the Congressman, but rather to the Legislative Director or Chief of Staff. Get to know those people by name, be friendly with them, not hostile.

Knowing their names can get you past the gatekeepers and to the people who have real or better answers. Then in the future you can call in with a friendly and confident tone and say “Yeah, this John Smith, is George available?”

You’re likely to be connected. When someone calls and just says “Can I speak to the Congressman?” that raises red flags immediately and we have to try screening you.

In-Person Advocacy

A face-to-face conversation with either staff or the representative will go much further. Visit the Congressman’s district offices which are much more approachable.

Every elected official feeds off of press. Track down your Congressman’s next public event or ribbon cutting and then show up. Have a conversation about what is important to you and ask them questions about what they’re doing about it.

If you don’t like their answers, then become a thorn in their side, and make sure they get press for it — social media is right at your fingertips, you are your own independent journalist with a small network of influence.

Get Involved

There are tons of worthwhile organizations that advocate for the environment. Get involved with one of them. People are much more effective when working together. Even a small group of organized and informed influencers can have a big impact and are much harder to ignore.

As a staffer, I’ve personally worked with a number of incredible environmental groups. They are filled with passionate and hard-working advocates or lobbyists (that word, lobbyist, isn’t a bad word–there are advocates for and against virtually every topic).

Find one you like and help ’em out:

- Sierra Club

- The Trust for Public Lands

- National Parks Conservation Association

- The Wilderness Society

- The Nature Conservancy

- Defenders of Wildlife

- The Ocean Conservancy

- Trout Unlimited

- American Rivers

Unite with Others

Collective efforts are heard louder than individuals. If you are a hiker or a climber, find common ground with hunters and fishermen.

While there may be issue areas that divide those two groups, there is much more that unites them.

Environmental protection and animals don’t recognize the borders of national parks or wildlife refuges, nor the border from one state to the other. Water quality, air quality, and so forth are important to all and go well beyond any borders.

Focus on areas of common ground between unlikely allies, and ignore differences or other points of contention as much as possible.

Be the Squeaky Wheel

So yeah, contact your Congressman and your Senator, but remember that they pay attention or take notice only in proportion to how well-informed you are and how much effort or noise you (all) make.

The squeaky wheel gets the grease in Washington, D.C.

If what you do takes only a few seconds and almost no effort, well, they are probably not likely to lend much credence to what you are saying.

They pay attention to their re-election chances, to money (from donors or what they’ve brought back to the district or saved), and to press (either positive or negative).

Their job, of course, is to work for all the constituents of their district, but they will focus their efforts on what they think will resonate the most with the politically active core group that will reelect them. That’s just the truth.

There is no reason to sit by silently if you don’t like what you see happening. Please make sure your voice is heard.

Resistance is not futile — it’s important.

How to Fight for the Environment

Look up who your Congressman and Senators are if you don’t know already.

The House of Representatives is easiest to focus on because they are, by design, more responsive to the will of the voters, with elections held every two years. Whereas the Senate is designed to provide a brake against popular sentiment (which can at times be irrational, uninformed, counterproductive, or even harmful) with their six-year terms.

Then take a minute to look up your Congressman’s record on environmental issues through something like the League of Conservation Voters.

Don’t like what you see?

Work to ensure that they are defeated in the next election.

Notice I said work. If you have money to donate, that’s great, but what’s even better than money is donating your time. Getting involved, talking with your fellow outdoor lovers, staying informed, and helping more pro-environment representatives get elected by knocking on doors or making phone calls.

Now is the time to get involved so you aren’t stuck deciding between two bad choices come election day. Find a champion of your causes now, then help them make it to Washington by donating your time and maybe your money.

Now is not the time to sit politics out. If you don’t participate, you’ve given them a mandate to do whatever they want without public oversight.

Will you get involved?

Share This

If you care about the environment and found this article helpful, please take a second to share this on Facebook, Twitter, or Pinterest.

Ryan

Latest posts by Ryan (see all)

- Kazakhstan Food: Exploring Some of its Most Delicious Dishes - August 7, 2023

- A Self-Guided Tour of Kennedy Space Center: 1-Day Itinerary - August 2, 2022

- Fairfield by Marriott Medellin Sabaneta: Affordable and Upscale - July 25, 2022

- One of the Coolest Places to Stay in Clarksdale MS: Travelers Hotel - June 14, 2022

- Space 220 Restaurant: Out-of-This-World Dining at Disney’s EPCOT - May 31, 2022

Comments 2

Dear Ryan,

Thank you for this explanation of how the DC process works, and practical, effective ways for concerned citizens to help save the environment.

Author

Thanks LouAnn for checking it out and leaving a comment — I really hope we can elevate the efficacy or our advocacy in the coming years.