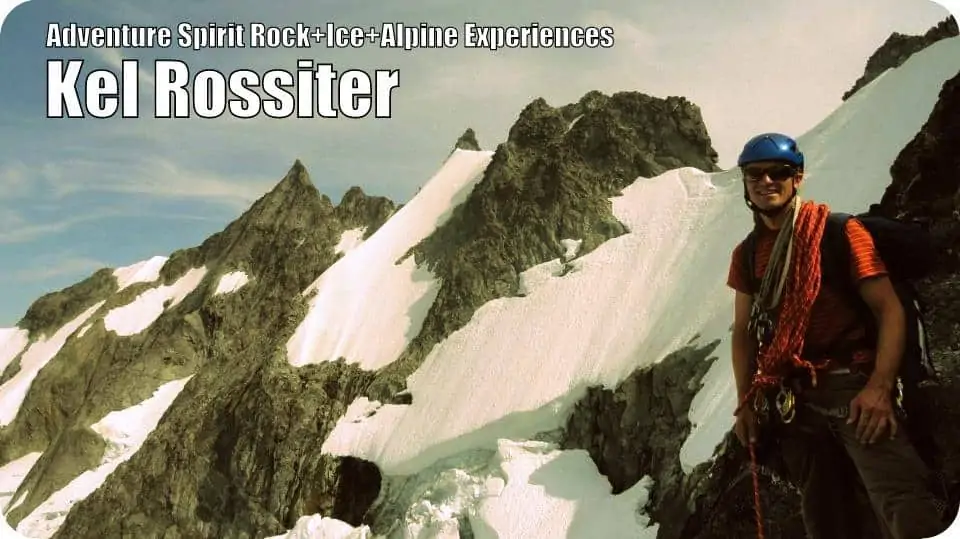

I recently had the opportunity to chat with climbing guide Kel Rossiter of Adventure Spirit Rock+Ice+Alpine Experiences about the world of climbing, adventure, and what it can teach us about life in general.

I’ve had the pleasure of climbing with Kel on a handful of occasions, a couple of times up in New Hampshire seeking out ice, and the last time was back in Washington State on the Torment-Forbidden Traverse.

Kel is an excellent guide and an all-around great guy, as well, and I’ve particularly enjoyed his approach to guiding and instructing clients (which is why I keep climbing with him!).

Read on for some profound insights about the nature of climbing, what climbing can teach us about life, how the public’s perception of successful climbers shapes climbing, and so much more!

Ryan: First of all, how did you get into climbing and what made you decide to pursue it as a career path?

Kel: I went to school in coastal Virginia (College of William and Mary) but amazingly they had a climbing course. I took it and it took me. Soon we were epoxying golf balls, bricks, roadkill, and whatever we could get our hands on to the side of the brick gymnasium.

As far as pursuing it as a career path, that line is about as wiggly as the trail down the Lower Kahiltna Glacier in early July. A quick read looks like this: a brief stint in the Army, a corporate job in Japan, back home as a freelance writer, living for a stretch at a Zen monastery, then off to work on a ropes course.

Thinking I was so lucky to get exposed to climbing in college, I decided I wanted to share that passion with others in a college setting. Those kinds of jobs usually demand a masters degree, so I got one at University of New Hampshire, returned to the Zen center for a year of gardening and meditation, then landed a great job as the Director of Outdoor Education at Georgetown University.

Those students and the experiences we had together were amazing! And DC is really an underrated outdoors town. But, ultimately my partner (and now wife) Alysse and I decided we wanted something different, so we came to Vermont.

After another stint in the college context, this time on the faculty of the Vermont State Colleges, I ultimately decided that college students shouldn’t be the only ones having all the fun, and I wanted to share the joy of climbing with learners of all ages and stages in life. Working as a guide-instructor is the perfect way to do that.

There it is—my whole life in a paragraph!

You are originally from Washington State but now call Vermont home… A lot of outdoorsy folks that I know want to make the shift from the East Coast to the West Coast. What made you head in the opposite direction? And is Vermont where you would like to stay?

I’ve got the best of both worlds now! From May to August, I’m out west guiding with my own company, Adventure Spirit Rock+Ice+Alpine Experiences, and with Rainier Mountaineering Incorporated (RMI)—that is absolutely the best time to be there—and for most of the remainder of the year, I’m in Vermont.

There’s a lot to like about the East Coast, the Northeast more specifically, and Vermont exactly. Vermont has what I have only been able to pinpoint as “a sense of scale.”

When I land in Seattle in May it always takes some time to transition. The mountains of the West match the mega-scale of everything: driving on eight-lane highways, filling up with gas at stations the size of an airport tarmac, and walking through supermarket cheese aisles straight out of the movie “Borat”.

I won’t even discuss the topless espresso stands… the Pacific Northwest is a great place to be for a few months every year, but I anticipate staying in Vermont. The prospect of a long-term future in Vermont makes me happy, but ultimately I like to remain open to possibility.

Do you feel that New England or Vermont, in particular, are overlooked in terms of their outdoor potential by the rest of the country?

So much the better! While the climbing current definitely flows east-to-west, those climbers that do swim against the tide do so with resolution.

They come out strong. They want to be here and they know what it offers. They are confident in their decision, content, and unconcerned by “what others are doing.” This is where they want to be. And those are the kinds of people I love being with.

No doubt, the range of options west of the Mississippi is quantitatively larger than those in the East, but in terms of density and accessibility the East Coast—and specifically—the Northeast, takes the climbing cake.

Relatedly, when I consider going out for a climb, I think about it terms of what I alternately refer to as the “car-to-climb-time ratio” and the “carbon-to-climbing footprint” and the Northeast definitely wins that math–and that math is important to me both as a person with a limited time on Earth and a concern for the Earth.

With a name like Adventure Spirit Guides, you must firmly believe in the powerful and defining role that adventure plays in our lives. But with conga lines to the top of Everest, tweets from the South Pole, Alex Honnold soloing the Triple Crown, and young kids completing the Seven Summits or climbing El Cap, has that fundamentally changed the concept of adventure and the world of climbing? What does adventure mean to you and what role does it play in your life?

Adventure is limited only by imagination. Imagination exists both within individuals and within cultures. Within individuals, I feel that adventure is expressed in terms of confronting unknown outcomes and dealing with possibility.

Culturally, we seem pretty infatuated with things like El Cap and Everest. It would be beneficial to individuals and cultures—and especially the climbing culture—if they were to infuse their adventures with more imagination. There is a whole world out there to explore.

People then try to make themselves look successful by climbing things that others think define success. There will always be what the masses do and then there will be what you do—exploring that is where the adventure begins.Kel Rossiter

I don’t feel that any of the examples you mention above really change “adventure” per se, they just reflect upon what we as a culture perceive or depict as an adventure.

Committed climbers traditionally have been something of a fringe movement in societies, as society doesn’t really value or reward the qualities that climbing demands. But society is attracted to those ideas and tries to appropriate the ideas and the terrain.

So you have a situation, interestingly, whereas climbing does become more popularized, those attracted to it bring in mainstream ideas about what constitutes success, setting up a strange “non-conformist conformity.”

People then try to make themselves look successful by climbing things that others think define success. There will always be what the masses do and then there will be what you do—exploring that is where the adventure begins.

As for the role adventure plays in my life, it plays a pivotal role in that climbing continually challenges me to be present. Because adventure involves the unknown, we must pay attention and be ready to respond to whatever arises.

Miguel de Unamuno said that “To fall into habit is to cease to be.”

That’s pretty strong language! I’ve got my habits and routines, and as far as any being exists independently of the social and material world (which isn’t that far), I’m pretty sure I exist. But, in broad strokes, he is speaking the truth.

Our routines become a shortcut to really thinking about and experiencing our lives. Adventure asks me to avoid that rutted path and to step into the bushwhack-backcountry of the considered life. Of course, the danger of the “considered” life is that one becomes so busy considering that he never takes action.

That will out-and-out kill you in the climbing context and will lead to a million tiny deaths in the everyday world. Adventure—and often climbing in my case—challenges us to fuse consideration with decisive action.

But it doesn’t have to involve swinging from ropes or scaling tall peaks: volunteering abroad, mentoring an ex-prisoner, or taking up improv comedy are among the myriad other ways I can imagine opening one’s life to consideration and action. I work to not be myopic or mono-dimensional, but for me, climbing has always been the go-to adventure I’ve used to frame my life.

If you could go back and give yourself advice when you were just getting into climbing, what you would you recommend? And what are some of the biggest pitfalls that newer climbers fall into that prove unproductive?

A Zen guy named Suzuki Roshi talked about the advantages of the “beginner’s mind” and it holds true in climbing. Beginners generally have the optimal frame of mind—they’re interested in exploring the excitement of climbing and what it can mean to them.

They climb up, enjoy the cool view, come down, and climb again. Later on, people often can develop all kinds of other stories about “how I should be climbing harder” or “reasons I’m not.”

Those stories often have unhappy endings. But the unhappiest endings are usually suffered by those who become way too wrapped around the axle about their identities as climbers. They begin to imagine that by becoming a better climber they will become a better person.

About ten years ago, [I think it was] Climbing Magazine that did a feature on the “50 Greatest Climbers Ever.”

Not surprisingly, many of them were now dead due to climbing. Also not surprising, several others had died via various other adrenaline-producing activities like driving fast cars.

What caught my attention was how many that had died by their own hand—suicide. I see that as yet more conclusive evidence that climbing better will not necessarily make you a better, happier, or more fulfilled person.

On the other hand, how you approach climbing definitely will. Adventure involves unknown outcomes.

Life has a known outcome—you will die.

Whether you’re a badass climber or a weekend warrior, we all return to the same valley. What you do in between, which is to say, how you approach climbing and how you approach life, is what matters.

For me, climbing has become a microcosm for life, a way to study the vast incomprehensibility of the universe through a finite lens. I’ve always found climbing helpful in that it helps me to understand life, but I’ve never thought that it should serve as a proxy for my life.

So, I guess the moral of the story here for me is “view climbing as a means toward fulfillment, but not the end of itself.” Now–damn!–if I could just roll up to the crag in a Maserati and fire trad 5.12s consistently life would be really great…

What are the three biggest benefits of hiring a guide such as yourself for climbers who have the fundamentals down but are looking to further progress as climbers?

My perception is that most people in the US view climbing with a guide as something you do primarily as a means to increase your safety. Safety is an important component, but there are two other huge—and often overlooked—benefits: progress, and then with it, enjoyment.

American and European attitudes toward climbing with guides seem to me to be fundamentally different. Americans have this kind of “do-it-yourself-rugged-independence” streak that makes them think that they only need a guide in situations where safety is a big issue.

People show up for a Rainier climb and explain, “My husband/wife said I could only do it if I went with a guide.” Otherwise, stand back, and “Watch this!” because they’ve got it. That’s too bad.

Paul Petzoldt (who started NOLS, the National Outdoor Leadership School) observed: “Most expert climbers who have been climbing for forty years are just amateurs repeating the same mistakes they made the first two years for the last thirty-eight.”

The result is one that all of us—totally including myself—have either seen or been directly a part of: meltdowns at the belay because the rope is a hopeless tangle, someone (typically the “leader of the day”) acting out because they are way behind where they need to be on the climb and they need an out, that same “leader” making rash decisions because they still want to complete the climb, etc, etc.

Whether it’s the Muir Route on Rainier, a winter Mt. Washington summit, the Dracula ice route at Frankenstein, the Whitney-Gilman rock route on Cannon, or any other “test grade” climb—I see people within groups making decisions or taking actions based on lack of appropriate skills (and perhaps more importantly correct application of skills) that are perhaps dangerous but are certainly alienating.

The part of their day I don’t see (but know from personal experiences) is the dispirited car ride home or time sitting in camp with your climbing partner, long-time friend, or cherished loved one, where excuses are made, positions justified, and wounds are licked.

The climbing may have been good, but its full potential was diminished. This could be avoided with a skilled instructor-guide.

A skilled guide is necessarily a skilled instructor—they should understand what your objectives are and if your objectives include learning the craft and enhancing your self-reliance in the mountains, they should be prepared to assist you in that process.

All too often, I see people up in the hills that don’t seem to be enjoying themselves because whatever techniques they’re using aren’t appropriate to the situation.

I see climbers running fifty-foot intervals on the spine of Disappointment Cleaver on Mt. Rainier. There are no fifty-foot crevasses on the Cleaver. In fact, there are no crevasses on Disappointment Cleaver—by definition, that’s what a “cleaver” is. There is, however, considerable rockfall and sliding dangers, enhanced by having fifty feet of rope out.

I see climbers on New Hampshire’s Presidential Traverse trying to tent above tree-line in worsening conditions. Perhaps that’s what they did during a similar summer experience and it worked. But this is a totally new, alien, and potentially dangerous environment.

I see climbers pitching out the steppy alpine ice route Shoestring Gully in the White Mountains. They know how to ice climb, how to multi-pitch, how to belay off the anchor, etcetera—but this is an alpine climb. They are trying to “hammer in a screw.”

The right technique is the right technique for the right situation. Sometimes inappropriate technique will get people killed—one of the most surprising things about my whole time in the mountains is not how often people die, but how seldom, given the missteps I see.Kel Rossiter

They may have the right tools but where they blow it is in the application of those tools across contexts. You may get a screw in with a hammer, but it won’t be pretty, or effective.

It is a good idea to read books, cruise the web, and view YouTube videos to enhance your climbing skills set, but ultimately—and this is perhaps one of the essential joys of climbing—it asks that you respond to each particular moment appropriately. The right technique is the right technique for the right situation.

Sometimes inappropriate technique will get people killed—one of the most surprising things about my whole time in the mountains is not how often people die, but how seldom, given the missteps I see.

So more typically, inappropriate application of technique just results in people having a frustrating day, distancing the people they are climbing with, thinking the problem lies within that particular climb or the nature of climbing itself and going home with no idea about how to rectify the situation.

There is a whole host of climbing books written about mistakes that result in people getting killed; few are written about the mistakes that result in frustrations and alienations, but proportionately perhaps those are more tragic.

It is difficult to teach a person who knows everything anything, but that’s where the ego leaves us most of the time. If people were open about what they didn’t know and sought out ways to rectify that, most tragedies of the large and small scale could be avoided.

Learning how to do that involves working with someone who is comfortable and skilled in that environment, who has worked with a variety of his/her own mentor-instructors, who has a repertoire of skills to draw from and isn’t grabbing a hammer to put in a screw because that’s the only tool she’s got in her box.

Mentoring with a guide can offer you that opportunity. If you work with a skilled guide-instructor, pay attention, ask questions, and challenge the answers.

You will have better experiences with your climbing, you will experience more growth in your abilities, you will have more time to enjoy the climbing itself, you will have more opportunities to enjoy positive moments with your climbing partners, and you will be able to more fully experience all that climbing has to offer.

What is the one thing you find yourself telling your various clients over and over again?

People inevitably ask “Have you climbed Everest?” or “Do you want to climb Everest?” When we were talking earlier about Alex Honnold, the Seven Summits, etc. I basically summed up my ideas about Everest, but I’ll add two things:

Climbing Everest is certainly a difficult challenge—of this I have no doubt. I have certain doubts as to whether it is the height of mountaineering achievement. But I can easily understand why the public sees it as such.

I think about this phenomenon the same way I think about jazz music. Lots of people love jazz music. Jazz lovers know its history, figureheads, pivotal moments, and masterpieces. Listening to the music, jazz lovers appreciate the complexity of expression and the creativity of particular players; they understand nuance, they recognize style.

I am not one of those people.

I have only a rudimentary appreciation of jazz. To me, most jazz sounds like the band is still tuning their instruments. And so if you asked me to name jazz players I think are good, I’d rattle off some list that’s been handed to me like “Miles Davis” or “Kenny G.” OK—not Kenny G—but take that general idea and extend it to mountaineering.

Then you can understand why the general public thinks Everest, the highest pile of rocks on the planet, is the be-all and end-all of climbing—and you can also begin to understand why that thinking may be quite limited.

How long will you continue to do what impresses other people versus what is original, unique, and interesting to you. Forget about what is impressive to other people—figure out what is impressive and beautiful to you. And then go do it!Kel Rossiter

The other question I have when posed with “The Everest Question” is “Where does this idea about climbing Everest come from?”

You may say it is something you want to do but is it really something you want to do? Where did the initial idea come from? You?

Or is it some culturally manufactured idea about what “the height of mountaineering is supposed to be” that you have consumed via books, the Discovery Channel, or mountaineer-motivational talks? And is that really the spirit of mountaineering and adventure?

How long will you continue to do what impresses other people versus what is original, unique, and interesting to you? Forget about what is impressive to other people—figure out what is impressive and beautiful to you. And then go do it!

As a side note: Apply this thinking to your whole life. Everest is just a placeholder for a whole range of similar societally-constructed mind traps.

What advice would you offer a new trad leader struggling to break through the mental aspects of trad leading?

The Rock Warrior’s Way (by Arno Ilgner) is a great book on this specific topic. I have found several portions of the book helpful and lots of people who read that book say they love it.

But before you run out a buy a copy, remember this: reading a cookbook gets you no closer to dinner and reading a diet book gets you no closer to thinner.

Don’t just read it—integrate it into your climbing. And if that goes well, consider integrating it into your life. Regarding the mental aspects of alpine mountaineering and summit climbing, I do have many more things to add, but that’s a work in progress—stay tuned!

What goals do you have for yourself both personally and professionally in the next few years?

I have many personal goals. I have professional goals too, but I’ve always felt that my professional goals should ultimately advance my personal goals, otherwise it seems that the tail is wagging the dog. So the personal goals reign supreme.

Of course, in guiding, personal and professional passions are often intertwined, so a lot of my interests span both areas.

On the more personal side, I’d like to explore mixed climbing more. I also have an avid armchair interest in gardening and foraging. It is something I was much more engaged with in the past, but nowadays my guiding schedule isn’t conducive to an agricultural schedule. I don’t have a clear plan for working that out, but foraging might provide an interesting alternative.

Community action is also important to me. Like agriculture, many community action opportunities demand that you have a schedule where you will be around in a predictable, stable way, which I don’t. I’ve found some options, like CRAG-VT (Climbers’ Resource Access Group of Vermont) that allow me to do that, and I’d like to find more.

Ultimately, all action is clouded if it is directed by a clouded vision, so my number one priority is and always will be to remain clear and present. I’ve found meditation helps with that; so I’d like to continue to expand my meditation practice.

Regarding professional aspirations, I certainly have many. Most of them center on improving the quality of my climber-clients experiences rather than growing my company or many of the seemingly typical business goals. It may sound cheesy or self-promoting to say that, but I think about it the same way I think about European versus American bakers:

I’m no pro in the subtleties of European culture and business, but I travel there quite a bit and my wife is Swiss, so I’ve got some idea about things. As nearly as I can tell, there are European bakers who have been baking for generations. They’ve got great recipes and they’ve got a successful storefront.

For generations, that storefront has brought in the money they need for their family to be happy.

Now, for the American baker that would all be well and good, but their next thought would be, “OK, now it’s time to open up another store”–or if that wasn’t their natural impulse, people would ask them, “So, when are you gonna open up another store?” and gradually that would seem like the obvious next logical thing.

For some reason, I’m not that logical! My guiding service is successful, it generates the income I want, provides me with the experiences and fulfillment I seek, and I’m able to provide income to some other colleagues as well. So, my focus is more on the quality of what we offer versus the quantity. That seems logical to me.

Linking the personal and the professional—as is the life of the climbing guide—and revisiting what I’d said when recommending The Rock Warrior’s Way book, I mentioned “a work in progress”: I’m currently cobbling together some ideas and experiences related to my summit climbing and what that can teach me about life. Perhaps that information could be useful to other people. I would like to share that with people and find out.

On that note, thanks for the opportunity of this interview and the chance it’s given me to reflect on climbing and how it’s informed and enriched my life. I hope that climbing will similarly inform and enrich the life of anyone else out there reading this interview. Onward & upward!

—

I’d like to sincerely thank Kel for taking the time to do this interview with me, and for his truly insightful comments about not just climbing, but life in general–a lot of food for thought!

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve climbed with Kel a handful of times now, and it has always been a really great experience–Kel is a patient and thorough instructor who has helped me progress a great deal.

If you’re interested in connecting with Kel about potential guiding/instructional opportunities in New England, Washington State, or elsewhere, be sure to visit http://www.adventurespiritguides.com for more info or just give him a call directly at 802-535-1498!

Read Next: Start Living a Better Story Today

Ryan

Latest posts by Ryan (see all)

- Kazakhstan Food: Exploring Some of its Most Delicious Dishes - August 7, 2023

- A Self-Guided Tour of Kennedy Space Center: 1-Day Itinerary - August 2, 2022

- Fairfield by Marriott Medellin Sabaneta: Affordable and Upscale - July 25, 2022

- One of the Coolest Places to Stay in Clarksdale MS: Travelers Hotel - June 14, 2022

- Space 220 Restaurant: Out-of-This-World Dining at Disney’s EPCOT - May 31, 2022